As I’ve mentioned before, natural disasters have consequences that can be immediate, long-term, political, social, or even literary. The most powerful volcanic eruption in more than 1600 years certainly counts as a natural disaster.

This year is the 200th anniversary of the catastrophic eruption of Mt. Tambora on the island of Sumbawa in what is now Indonesia. The category scale for volcanic eruptions is 1-8, with category 8 being the most powerful. Mt. Tambora in 1815 was a category 7. For comparison purposes, Mount St. Helens in 1980 was a category 5.

Aerial view of the caldera of Mt Tambora at the island of Sumbawa, Indonesia. Photo Credit: Jialiang Gao (peace-on-earth.org)

Most people have heard of the eruption of Krakatoa in 1883, mostly because communications were more advanced at the time and there was almost immediate information available globally. The Mt. Tambora eruption was ten times more powerful than Krakatoa, the largest eruption since 180 CE.

Mt. Tambora was originally 13,000-14,000 feet high, but the blast reduced that by 4,000-5,000 feet. The volcano spewed ash into the upper atmosphere, pyroclastic flows reached the sea 25 miles away, there were tsunamis, ash rained down for weeks, and several feet of ash were floating on the surface of the Indian Ocean.

An estimated 10,000 people died instantly and another 90,000 died from starvation and disease. Freshwater was contaminated and undrinkable. Crops and forests were either burned or smothered, so there was an immediate food shortage.

But this eruption’s claim to fame is the long term effect on the weather. I think the phrase “perfect storm” is overused, but there were other contributors to the amount of poison in the atmosphere. Between 1812 and 1814 there were four category 4 volcanic eruptions in the Caribbean, Indonesia, Japan and the Philippines. Without the pollutants already in the atmosphere, it’s possible the long term weather effects from Mt. Tambora alone wouldn’t have been so pronounced.

The summer following the eruption, 1816, is known as the Year Without a Summer. Europe and North America had frost and snow throughout the summer. Not just a trace of snow that quickly melted, but 6-18 inches. It rained for 8 weeks non-stop in Ireland. The atmospheric conditions disrupted the monsoon seasons in China and India, resulting in torrential rains and flooding.

In North America and Europe, 1816 was the shortest growing season on record. Crops were lost due to both the lack of sunlight and the near-constant frost. Because there were fewer crops, the prices for any available food increased. Lakes and rivers were frozen, further reducing available resources.

Western Europe had just been through twelve years of the Napoleonic Wars and the people were already suffering from food shortages. With famine comes disease and social unrest. There was a typhus epidemic in Ireland precipitated by the famine that claimed an estimated 100,000 lives. A cholera epidemic began in Bengal in 1817 and spread around the world throughout the 19th century, killing millions.

While the tragedy of this catastrophic event is obvious, there were also some positive effects. Nobody knew at the time, actually nobody knew for more than a century, why this strange weather was happening. In the United States, many people went west in search of better land, and weather, to farm, in the beginnings of the westward migration. Joseph Smith left Vermont to go west and later founded the Mormon religion.

Whaling captains began noticing a loss of sea ice near Greenland and icebergs floating farther south. This led to the hope of finally finding a northwest passage, which led to the age of Antarctic exploration.

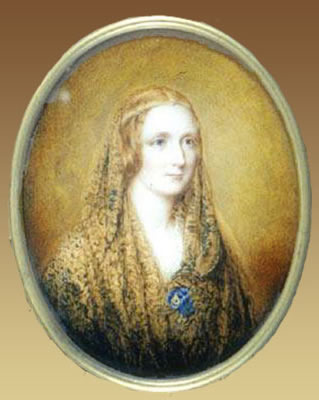

And most famously, Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin (1797-1851), soon to be Mary Shelley, wrote Frankenstein: or, the Modern Prometheus. Godwin and some friends, including the Romantic poets Lord Byron and Mary’s soon-to-be husband Percy Bysshe Shelley, were staying near Lake Geneva, but were kept indoors by the incessant rain and stormy weather. To pass the time they read German ghost stories, and then agreed to a contest to see who could write the scariest ghost story. Mary Shelley was only 18 that summer when she began writing this classic novel, which was published in 1818.

Reginald Easton painted this miniature portrait of Mary Shelley, on a flax coloured background. It incorporates a circlet backed by blue, the same seen in the Rothwell painting and a shawl. Attribution: Reginald Easton (1807-1893)

If you’re interested in more information about the eruption of Mt. Tambora and all that happened globally as a result, there are several recent books written on this topic. Since I haven’t read any, I won’t recommend any one in particular. I will include this link to one of the best articles I’ve read on the subject by Gillen D’Arcy Wood. He also wrote the book Tambora: The Eruption That Changed the World, published in 2014.

Love the worldwide connections that you found Cathy!

Thank you! Weather is an amazing thing, always reminds me of the butterfly effect. I remember when we were flying back from England to New York City a full year after Mount St. Helens erupted, and the pilot pointed out that you could still see stuff in the atmosphere. Amazing.